Teens in the Universe (1974)

Growing up, I had a varied media diet. On the radio, I’d catch broadcasts of local FM stations (and record mix tapes with my favourite bangers, which were all awful), sometimes switching to talk radio and even the BBC. VHS rental was a huge thing, all of the tapes of course being pirated and dubbed at different levels of amateur production. On Lithuanian channels, I’d watch old Jackie Chan movies, original Dragonball cartoons, Takeshi’s castle, and the odd Mexican soap opera (I still occasionally hum the tune to La Intrusa). And via an illegal TV antenna, we had access to Cartoon Network, which was the best English teacher my generation could have asked for.

But there was one medium that would broadcast stuff from a bygone era. Russian cinema channels. They had a roster of 20-30 Soviet-era oldies on repeat - movies that people who grew up in the 1960s-1980s knew by heart. Some of those comedies still hold water and rewatching them now it’s fun to notice the thinly veiled criticism of the absurdities people had to accept back then.

As a kid, I found some of those comedies amusing, but the stuff I was really attracted to was sci-fi. Apart from the adventures of Alisa Seleznyova (above), Tarkovsky’s Solaris and Stalker, and a couple of other titles, I don’t remember much today. One movie that did survive in my memory is Teens in the Universe, the second film in the Moscow-Cassiopea dilogy. This week, I decided to rewatch the movie and share some observations on a Soviet cinematographic attempt to make a space exploration flick for kids.

Time works differently, Einstein

I haven’t watched the first movie in the dilogy, but the second part can be viewed as a standalone. The backstory is simple. In the first movie, Earth received a distress signal from the constellation of Cassiopea, and a crew of Soviet children was assembled to answer the call. As the journey was expected to take 27 years, the plan was for those kids to reach the age of 40 by the time they get to their destination.

The fun starts with the opening titles. One of the people listed there is a head consultant who’s an actual cosmonaut (remember, the Soviets had cosmonauts, not astronauts). The viewer is also hit with some pretty good 70s electronica.

The movie opens with a scene where one of the kid’s relatives celebrate his 40th birthday. The atmosphere is solemn and there’s an empty chair left for little Pavlik. He’s not dead, but the parents accept that they’ll probably never see him again. A mysterious Soviet functionary appears out of nowhere and tells everyone that the kid is actually only turning 14 that day. Einstein’s name is dropped, and everyone accepts that the boy hasn’t aged.

The first real gag of the movie happens. We see a box of long nails and a slip of paper saying “Pavlik’s hobby - nails that Pavel Koselkov loved to nail”.

Kids in space being kids in space

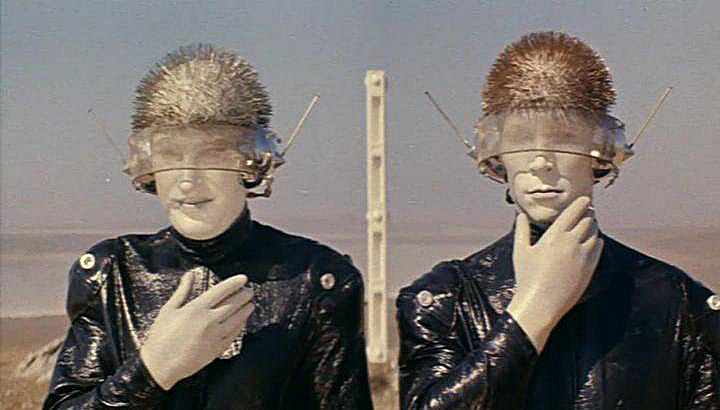

In the next few scenes, we are reacquainted with the kids on board the ship. They all wear funny jumpsuits, and apart from the funny kid (a specialist in extraterrestrial civilizations and inventor of some super glue) and the goody-two-shoes girl, I have trouble telling them apart. On board, they have a simulator to recreate different places on Earth. They try simulating the flat of the boy celebrating his 14th birthday, but the plan backfires pretty quickly. Thinking of home only makes everyone sad.

The goody-two-shoes girl makes everyone vow never to remind anyone of home. One of the kids protests, saying that it’s impossible not to think about home. The kids are playing the guitar and singing a song about space exploration.

Say what you want about propaganda-infused art, having a children’s song about exploring space is cool. And the song is pretty sad, it’s all about the nostalgia one feels after leaving Earth. “The stars probably won’t accept us” is repeated in the chorus several times.

After a few filler scenes, we see the kids trying to choose who will explore the planet. Funnily, even though they’re all on the same small ship, candidates dial-in via a TV screen. It’s prescient how in 1974 they predicted the adolescent obsession with screens and streaming. The funny boy reminds everyone he’s the only specialist on extraterrestrial civilizations and also the inventor of some cool glue.

A little bit of romance ensues when the captain suggests they call the planet after the girl who descends there first.

Brave new world

Three members of the crew land on the planet. No precautions are taken, as the three kids (funny boy, goody-two-shoes girl and birthday boy) step foot on the surface of an unknown world. One of the kids is super excited, sending echoes across the planet. The world looks barren and empty.

The funny boy announces he’s going for a run. Taking a leak on a new planet? Every little boy’s dream. We see the boy stand by some white structure (poor man’s 2001: A Space Odyssey obelisk). Of course, he takes a felt pen and writes “I WAS HERE” on this mysterious structure.

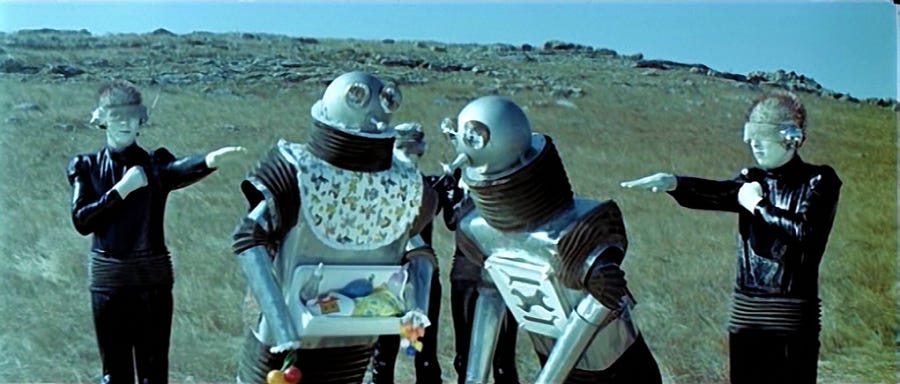

We then get to meet weird humanoids that communicate by whistling. Luckily, the boy has a universal translator as part of his spacesuit.

“Earth-peace-friendship. the square of the hypotenuse is equal to the sum of the squares of the other two sides.” This is how we, as a species, establish contact. With Pythagorean geometry.

The boy writes the formula on the white pillar. Incoming gag! He makes a mistake in the formula, only for the humanoids to correct him.

After a few interactions with the whistling humanoids (who are actually robots), all three kids end up in a white room drinking juice that comes from a hollow box in the middle of the room. They become more relaxed, as if the juice was drugged. Might this be a reference to Brave New World (parts of it were published in Moscow in 1935)? Perhaps. Perhaps not. Robots appear on screen eerily telling the kids they’ll make them happy, happy, happy…

Sidenote. One of the kids compares the taste of the drink to mango. A quick Google search revealed that imported canned mango juice was a thing in the USSR.

Meanwhile, the mothership comes in contact with a satellite that carries the last survivors of the alien civilization. We learn that the robots were created to make everyone happy, but they went too far. By removing flaws, they turned those aliens into beings devoid of feelings and desires. As a result, aliens would just linger in bliss and never reproduce.

On Earth, the mysterious functionary we saw earlier tries to help people at flight control to establish contact with the ship. Then, in a truly retrofuturistic fashion, he takes out a notebook with codes for planets and constellations and dials Cassiopea from a dial phone.

They use a port-cigar as a screen (like a flip phone). The connection is one-sided, but at least they can see the kids.

Kids outsmart the robots

As the trio left on the planet understands that the robots are up to no good, they plan their escape. The way they get rid of robot guards is hilarious and reminds me of some unconventional solutions in 90s point-and-click and RPG games. They ask robots a simple kids’ riddle that their minds can’t comprehend. It doesn’t translate well, but you can imagine it being “Why was six afraid of seven?” This literally fries their brains.

This trick works on lower-level robots (Implementers) but fails to impact their masters (Commanders).

It’s all shenanigans after this point, so I’ll just pepper a few highlights (note some popular tropes seen in today’s cinema):

- Robots engage in banter, as if they were factory workers

- Two robots swap heads (because the mechanic made a mistake)

- After frying the brains of two robots, the kids take their clothes and act as robot guards

- Commander robots want to relieve the kids of “capacity to love, sorrow, self-doubt”, while also removing their appendices

- Remember one boy’s love for nails and the other boy’s superglue? Well, turns out they’re both Chekhov’s guns that help them escape

- The only two good robots are a defective robo-nanny (she even has a piece of tablecloth fashioned as an apron) and this movie’s version of C3PO. The movie, of course, pre-dates Star Wars.

After the bad robots are defeated, the weird Soviet functionary appears asking the kids if it isn’t time to go back to Earth. FIN!

You can view the movie in its entirety here:

Some thoughts after rewatching the movie

After seeing all the costumes, the dances, the disco music, the interactions between the robots, my first thought is how this movie can be interpreted as, well… very queer. Interestingly, googling TEENS IN THE UNIVERSE + LGBT landed me on a pretty homophobic article bashing Western series and cartoons “corrupted by gay propaganda”. In that article, the movie TEENS IN THE UNIVERSE was presented as a positive example of a pure and good Soviet movie that taught kids proper values.

My second thought was “Is this really sci-fi?”. One article in Russian (which didn’t link to any primary sources, I’m afraid) mentioned that the movie was pre-screened for Leningrad’s sci-fi club, and was bashed by them for not being sci-fi enough. I think there is some merit to their criticism, as the story’s moralistic premise would have worked in a fantasy setting. Replace robots with evil witches, science with some curse, and voila - you have a story of feelings being important.

My third thought was “Did it age well?” Of course, it didn’t, but why do we expect things to “age” well? Books, movies, songs and other forms of art need to age. And there’s something beautiful in the way this movie aged, in particular. The robot-nanny with the metal carriage, the guy calling a distant galaxy via a dial phone, the kid writing “I WAS HERE” on the ruins of an ancient alien civilization. All of this puts a smile on my face and could probably be interpreted and analyzed to death. But I’m not an academic. I simply derive pleasure in noticing things and writing about them.

Member discussion